Bridging the Gap - Solution

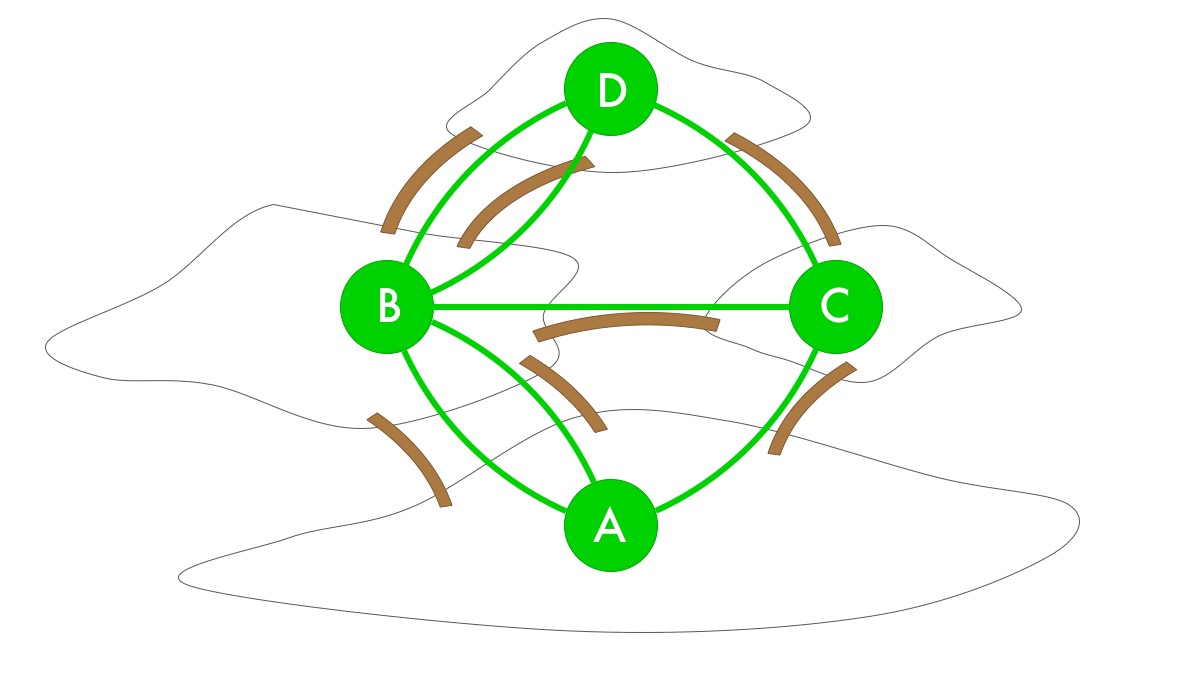

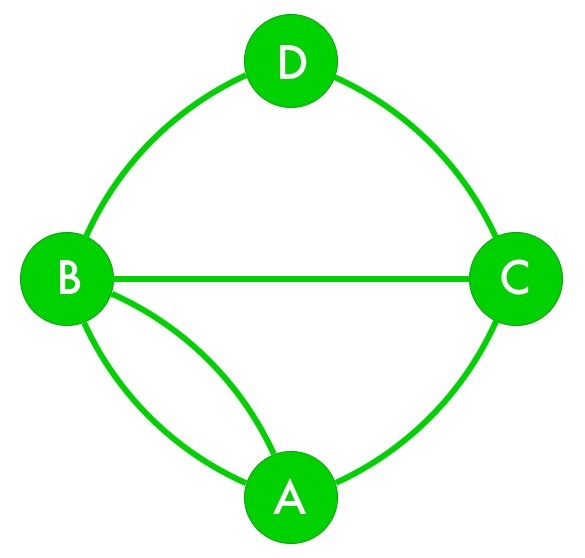

a. After a bit of thinking, the first thing we notice about this problem is that the bridges are the only things that matter: the shape and size of the islands are irrelevant. So we can simplify each terrestrial region down to a single point – let’s call the points A, B, C, and D – and let each bridge correspond to a line between two points:

In fact, we can now get rid of the map entirely and just work with the points and lines:

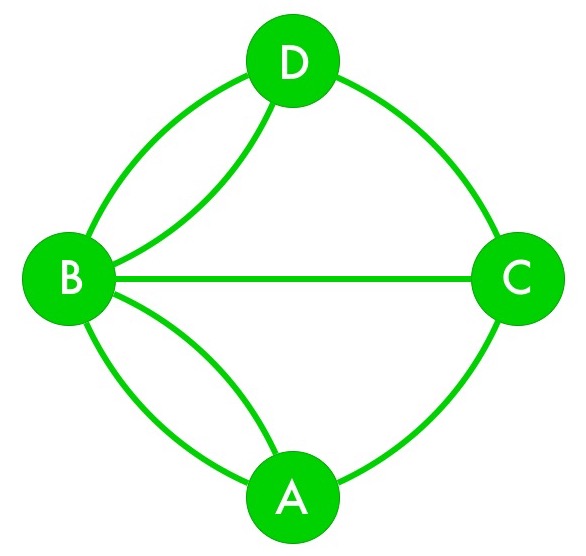

What we just made is called a graph: it has a set of nodes and a set of edges connecting the nodes. Any tour route will start at one of the nodes and trace a set of connected edges before ending at a (possibly different) node.

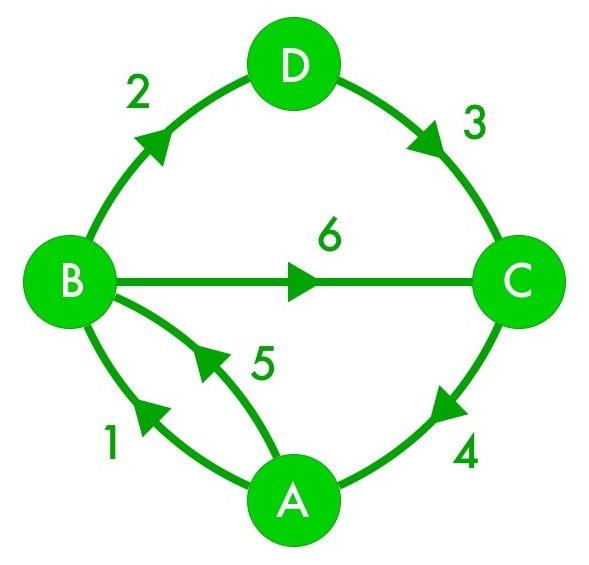

After playing around with this graph for a while, we might notice the following: whenever we pass through a node in the middle of a tour route, we take one bridge into the node and another bridge away from it. This tells us something very useful: except possibly for the start and end nodes, every node will have an even number of traveled-over edges connecting to it. For instance:

This isn’t a solution, of course, because it skips two bridges. Notice, though, that node B has 4 traveled edges connecting to it, and nodes C and D each have 2 traveled edges connecting to them. (A happens to have an even number of traveled edges connecting to it since it’s both the start node and the end node.)

If the graph has a solution to Morton’s tour route problem, then, it must have at most 2 nodes (the start and end nodes) with an odd number of connected edges. As a result, we can say the following for certain: Any graph where more than 2 nodes have an odd number of connected edges cannot have a solution to Morton’s problem.

Looking back at our bridge graph, we now see that all four nodes have an odd number of bridges connecting to them. So in the current bridge arrangement, it is impossible for Morton to find a tour route that crosses every bridge exactly once.

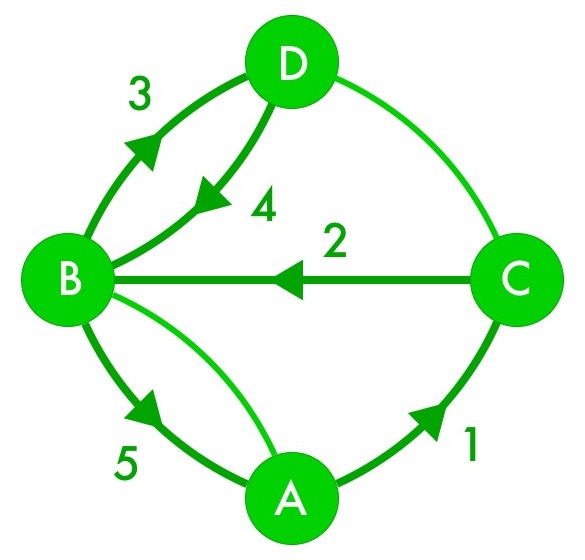

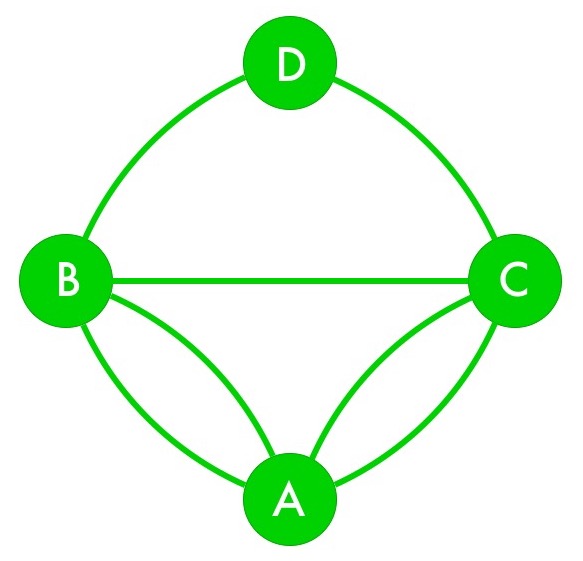

b. With the northwesternmost bridge gone, the bridge graph now looks like this:

Nodes B and D now both have even numbers of edges connecting to them. Nodes A and C, though, both have odd numbers of edges connecting to them, so they both have to be endpoints. Now a bit of experimentation leads us to one solution, starting at node A and ending at node C:

(You may have found a different solution than this one. That’s great! How many more solutions can you identify?)

Since both nodes A and C have to be endpoints, Morton can build a tour route that crosses each bridge exactly once, but not one that starts and ends at the same node.

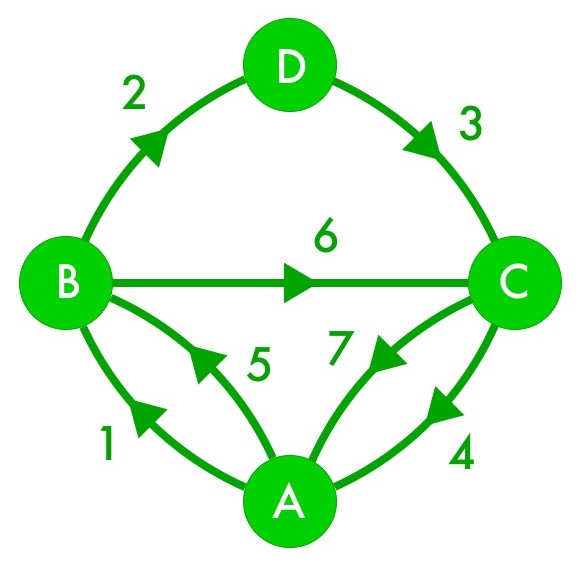

c. To make it possible to complete the bridge tour with the same starting and ending node, all nodes must have an even number of bridges connecting to them. The only way we can do that is to connect nodes A and C with another bridge:

And indeed, a bit of experimenting turns up a complete bridge tour with the same starting and ending node A:

This, then, is what Morton should propose at the town hall meeting.

By the way, a path through a graph that crosses each edge exactly once is called an Eulerian path, and an Eulerian path that also starts and ends at the same node is called an Eulerian circuit. Euler (pronounced “oiler”) was the mathematician who first worked on this problem, which became the field of graph theory. We just rediscovered Euler’s result ourselves!