Prime Numbers

It’s pretty simple to multiply two numbers and get another number.

$$ 2 \times 3 = 6 $$

Here’s a question for you: What happens if we try to go the other way? For instance:

$$ 15 = ? \times ? $$

With a little thinking – remembering times tables, experimenting a bit – we can figure out the answer.

$$ 15 = 3 \times 5 $$

What we just did is called factoring. Instead of taking two little numbers and multiplying them to get a bigger number, we took a bigger number and broke it into two little numbers.

Let’s give this one a try:

$$ 11 = ? \times ? $$

No matter how hard we think, we can never come up with two smaller numbers that multiply to $11$. The best we can do is to say $11 = 1 \times 11$, but we didn’t really break it down into anything smaller that way. When a number doesn’t have any factors besides $1$ and itself, we call it a prime number. When we can break it up, we call it a composite number. $11$ is a prime number. $15$ is a composite number.

Here’s another one to try:

$$ 24 = ? \times ? $$

With a little thinking, we might come up with this:

$$ 24 = 4 \times 6 $$

But what happens if we go a step further? What if we tried to factor the factors?

$$ 4 = ? \times ? $$

$$ 6 = ? \times ? $$

Try to solve this on your own first. I’ll wait.

…

…

…

Got it? Here’s the answer:

$$ 4 = 2 \times 2 $$

$$ 6 = 2 \times 3 $$

So we can write 24 like so:

$$ 24 = 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 3 $$

We can’t break these factors down any more ($2$ and $3$ are prime), so that’s as far as we can go.

“Wait a minute,” you might say. “I didn’t get $24 = 4 \times 6$. I got $24 = 8 \times 3$ instead. Am I wrong?”

Good point. $24 = 4 \times 6$ isn’t the only way we could have started factoring $24$. You’re not breaking it apart wrong; you’re just breaking it apart in a different way. So let’s go down that path and see what we find.

$$ 24 = 8 \times 3 $$

$$ 8 = 4 \times 2 $$

$$ 4 = 2 \times 2 $$

We get:

$$ 24 = (4 \times 2) \times 3 = (2 \times 2) \times 2 \times 3 $$

$$ 24 = 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 3 $$

Hm, this is interesting…

$$ 24 = 4 \times 6 = 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 3 $$

$$ 24 = 8 \times 3 = 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 3 $$

We get the same breakdown both times, even though we started in two different ways. Is this a coincidence?

As it turns out, it’s not. Anytime we break apart a composite number into its prime factors, no matter what path we take to get there, we’ll always arrive at the same result. In other words, every composite number has a unique prime factorization. This fact is so important it’s called the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic.

Prime numbers are arguably the most fundamental building blocks of an area of math called number theory. But even as fundamental as they are, they’re also surprisingly mysterious. They’ve fascinated and puzzled people through the ages, and even today we don’t know everything about them.

Let’s dive in and explore these special numbers. We’ll start by asking: How do we find prime numbers? Can we make a list of them?

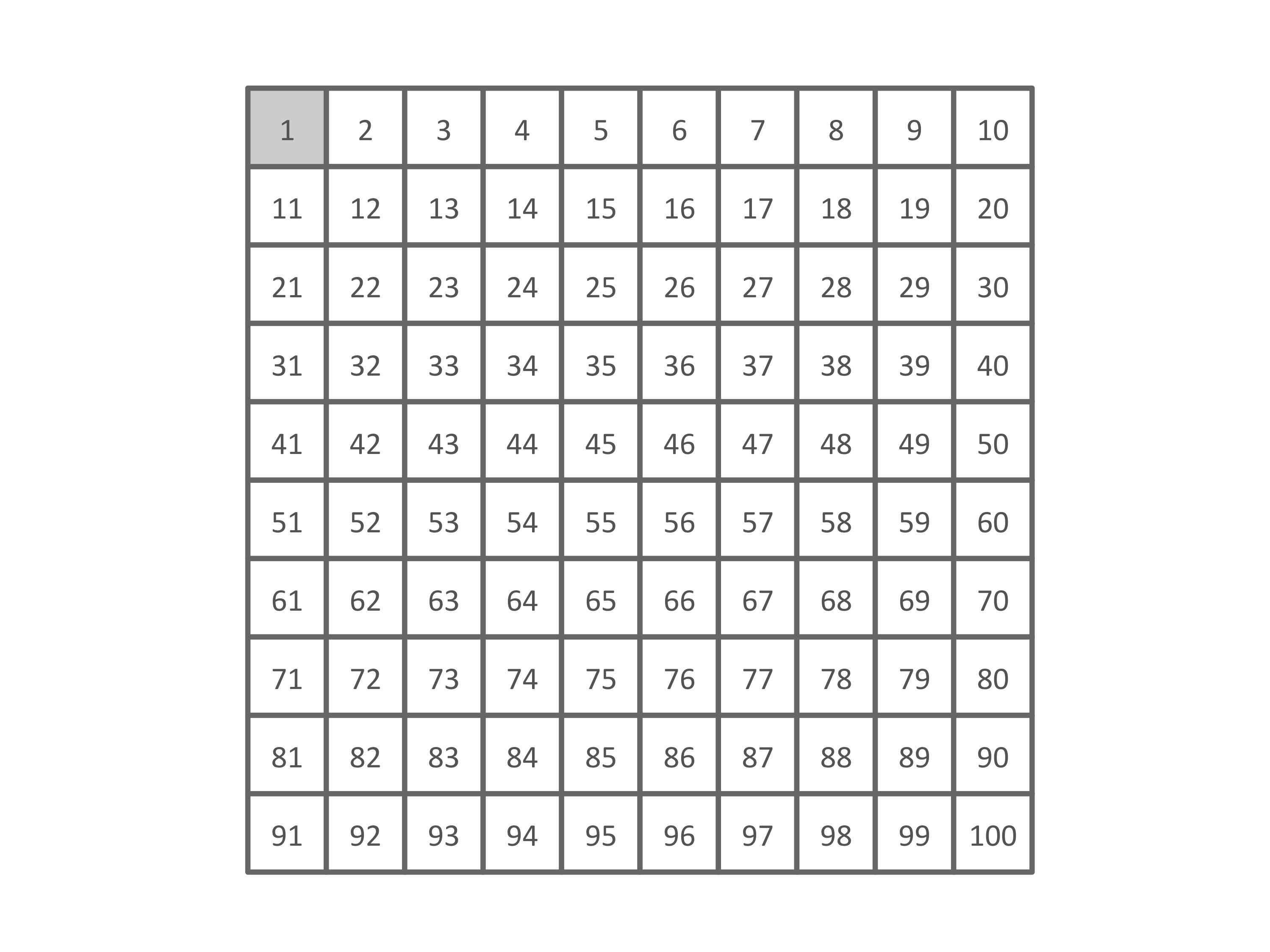

Okay, let’s try. We’ll start at the beginning, at the number $1$. $1$ is funny – it’s actually not a prime number. Remember, our definition says that a prime number’s only factors are $1$ and itself, and “$1$ and itself” in this case means “$1$ and $1$,” which doesn’t really fit the definition. It’s not composite, but it’s not prime either. So we leave out $1$ from our prime number list.

Now $2$. $2$ is the first prime number. It’s also the only even prime number. (Can you figure out why?) Then comes $3$, which is also prime. $4$ is not prime, since $4 = 2 \times 2$. But $5$ is a prime number: it’s not divisible by any of the primes smaller than itself, so we can’t break it up any further. $6$ is not prime, as we saw before: $6 = 2 \times 3$. But $7$ is prime; you can’t factor out any $2$, $3$, or $5$ (the primes smaller than $7$). $8$ is not prime; it’s divisible by $2$ as well. $9$ is not prime either, since $9 = 3 \times 3$. Neither is $10$, since it’s also divisible by $2$.

This is getting a little tiring. Every time we test a number to see if it’s prime, we have to check all the prime numbers smaller than it to see if any of them are factors. We’ve only checked the numbers up to $10$ so far, and we only have four primes: $2$, $3$, $5$, $7$. This might take an awfully long time if, for example, we were trying to see if $1,000,003$ is prime. There’s got to be a better way to find prime numbers.

Fortunately, we can take a couple of tactics to make our search easier. One way we can do this is by using what’s called the Sieve of Eratosthenes, named after a fellow from ancient Greece. Here’s how it works.

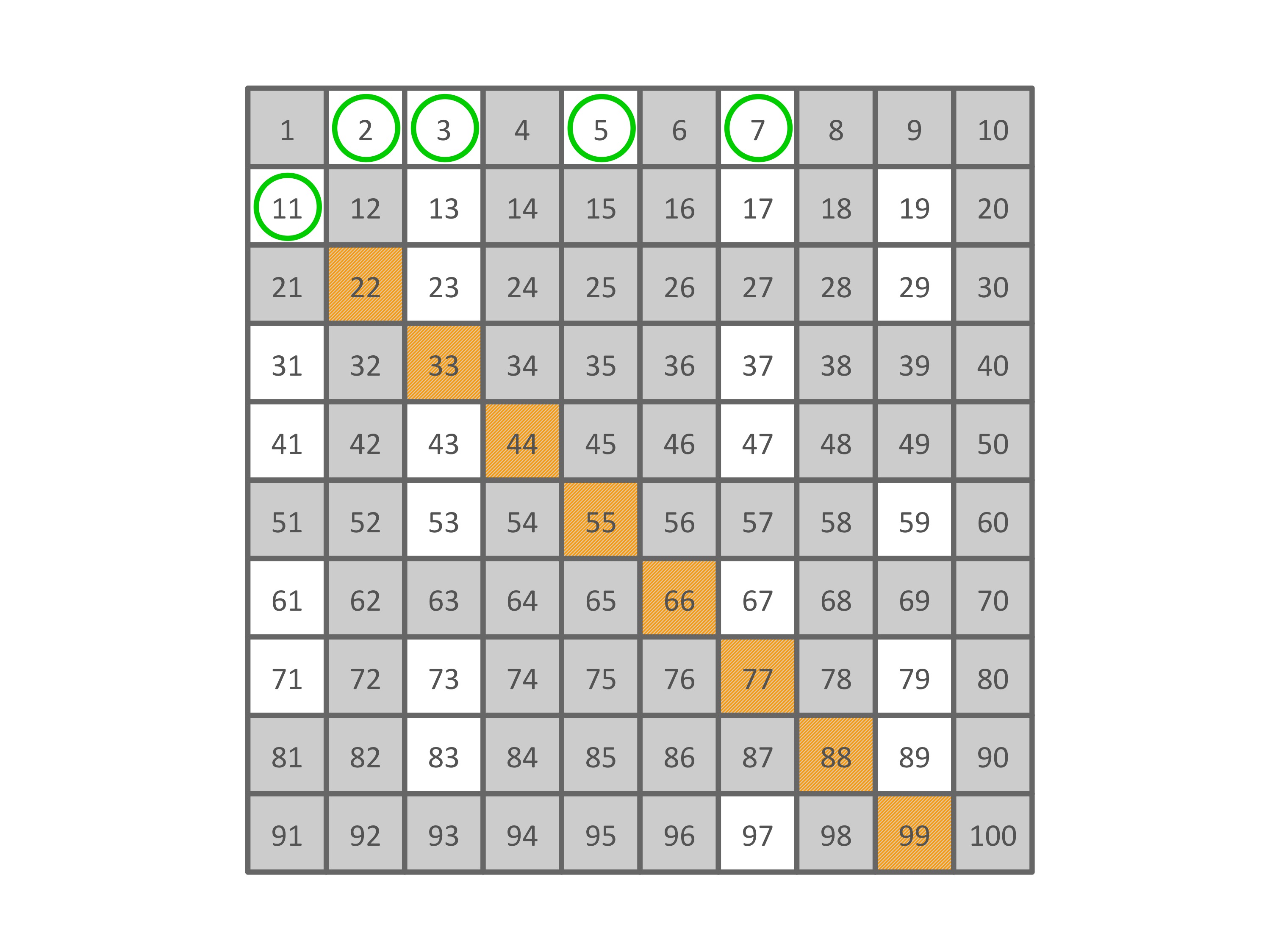

We start with a grid of all the numbers we want to test. (We’ll gray out $1$ because we already know it’s not prime.) For now we’ll just go up to $100$, though you can extend the grid as far as you want.

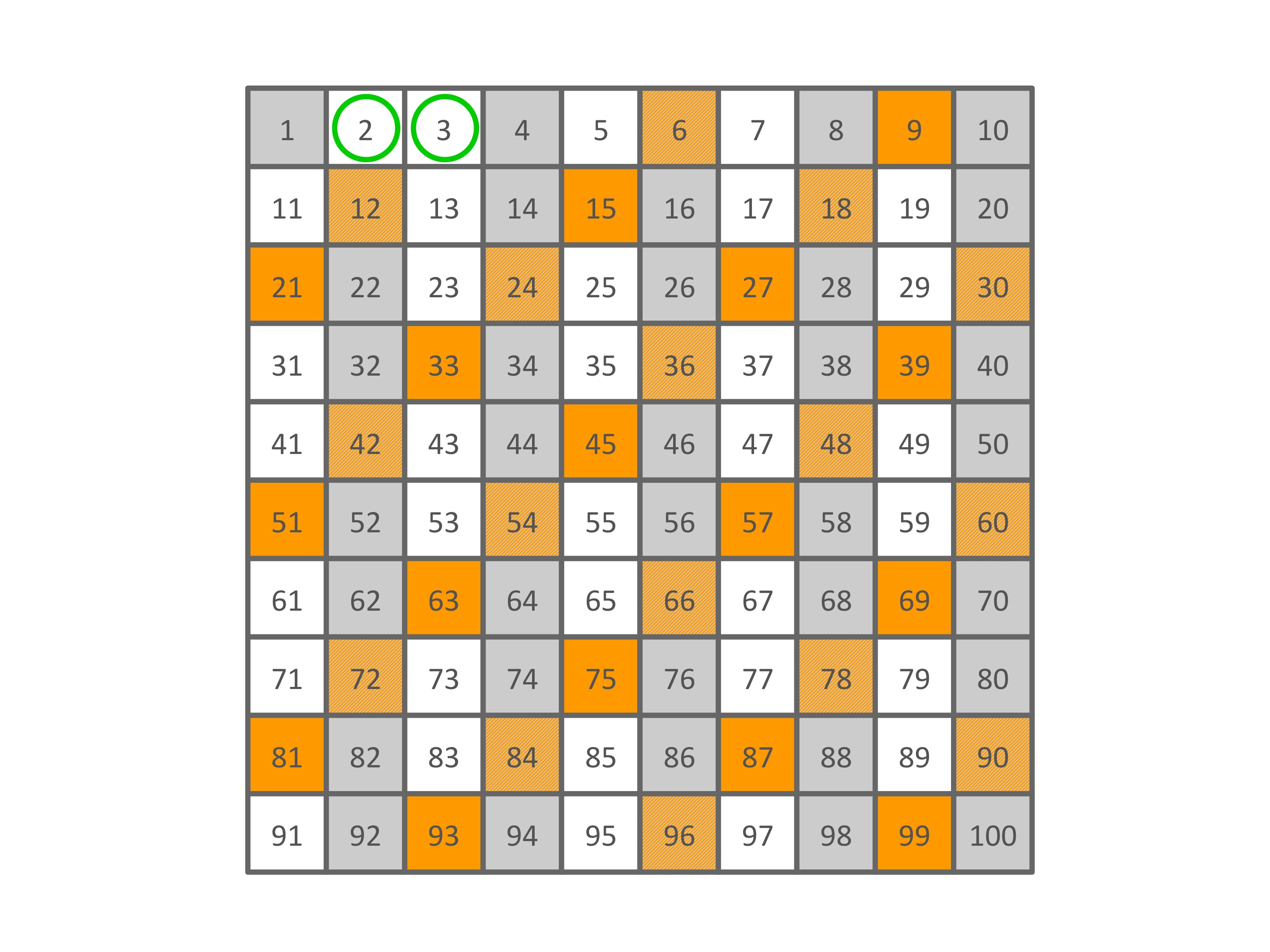

We first circle the first prime number, which we already know is $2$:

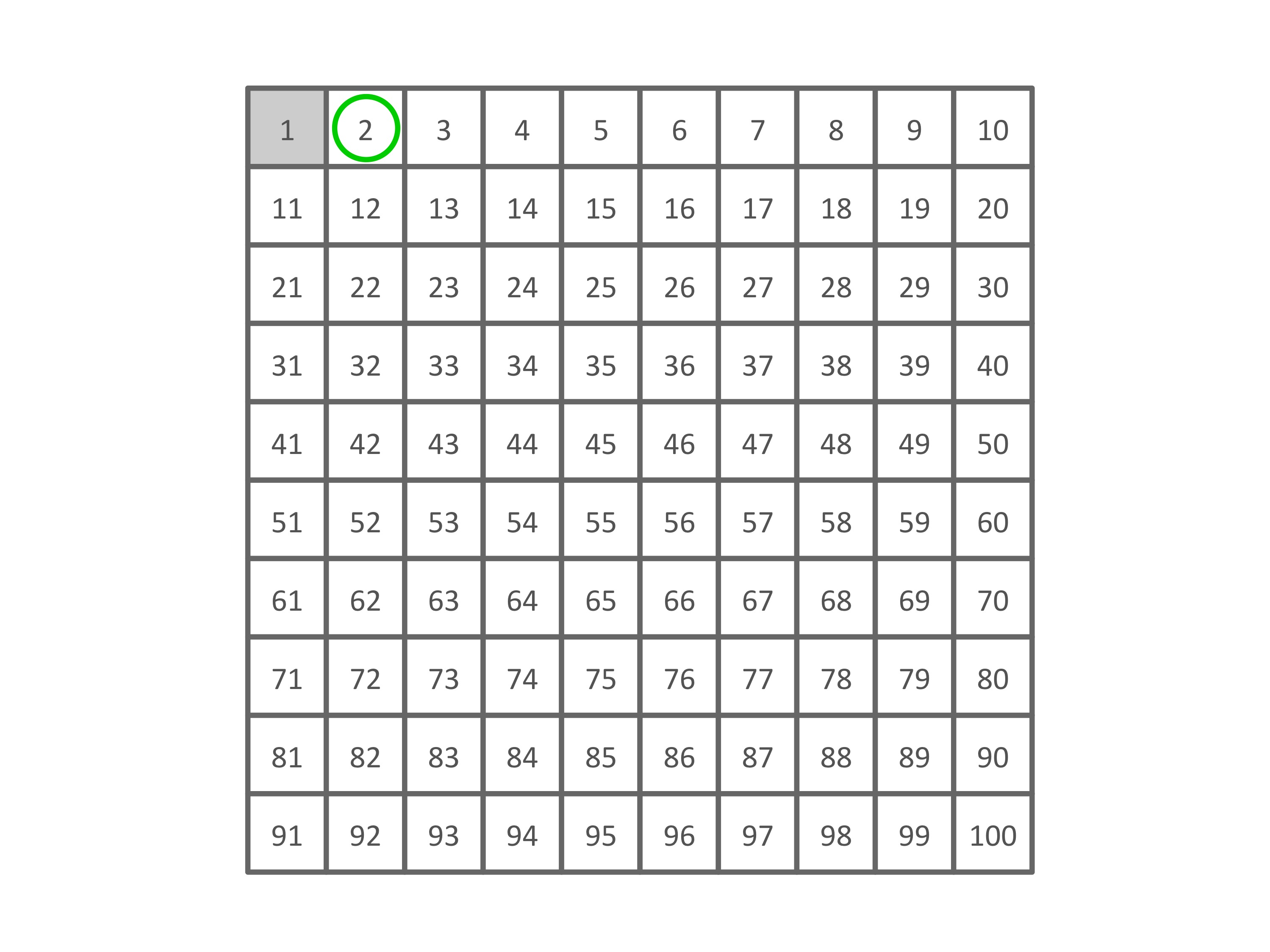

Now we count off every other number, shading them because we know they’re divisible by $2$ but they’re bigger than $2$:

Right after $2$ is a number we haven’t shaded: $3$. We circle this prime:

And then we shade every third number, thus eliminating all composite numbers divisible by $3$. We might run into a number that’s already grayed out, and that’s fine – it’s already been marked composite, and composite it shall stay.

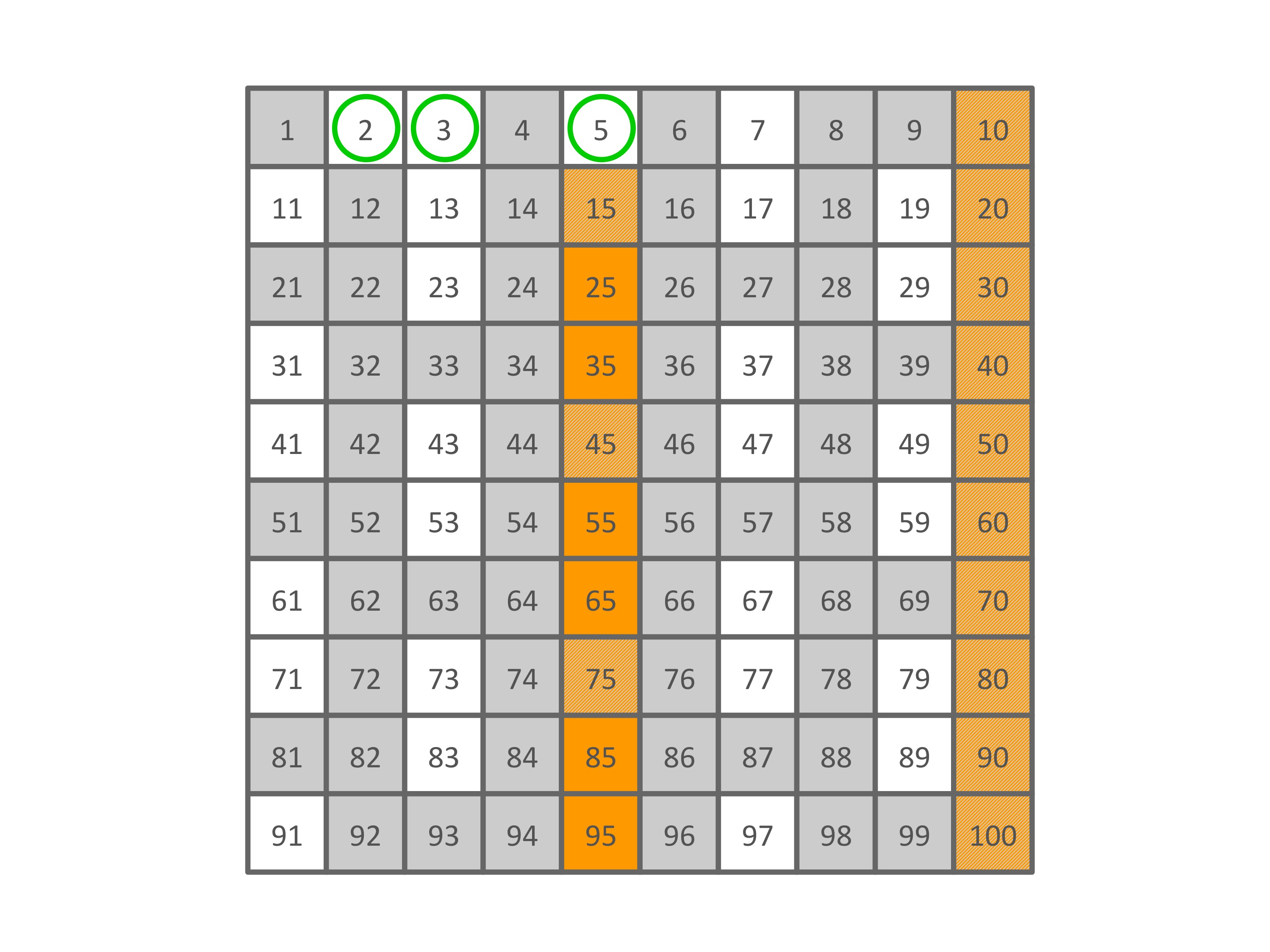

The number right after $3$ is grayed out, which means we’ve marked it as composite. (And it’s just as we expected, since $4 = 2 \times 2$.) So we skip over it and head to the next open number: $5$. We do the same thing, circling it and shading all its multiples.

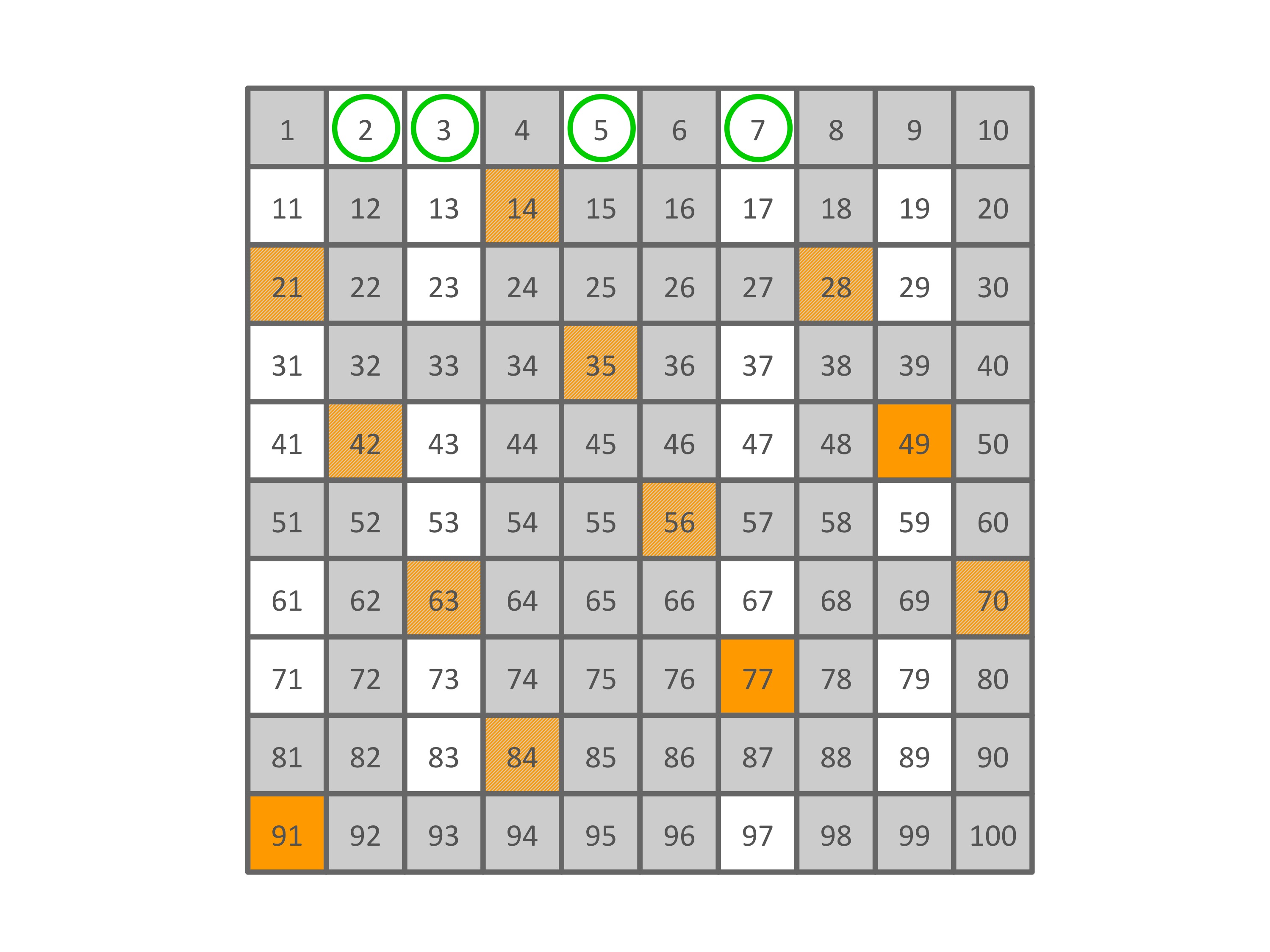

Onward we go. $6$ is grayed out, so we skip it and go to $7$. As before, we circle the prime and shade its multiples.

Now we skip over $8$, $9$, and $10$, and find that the next prime is $11$:

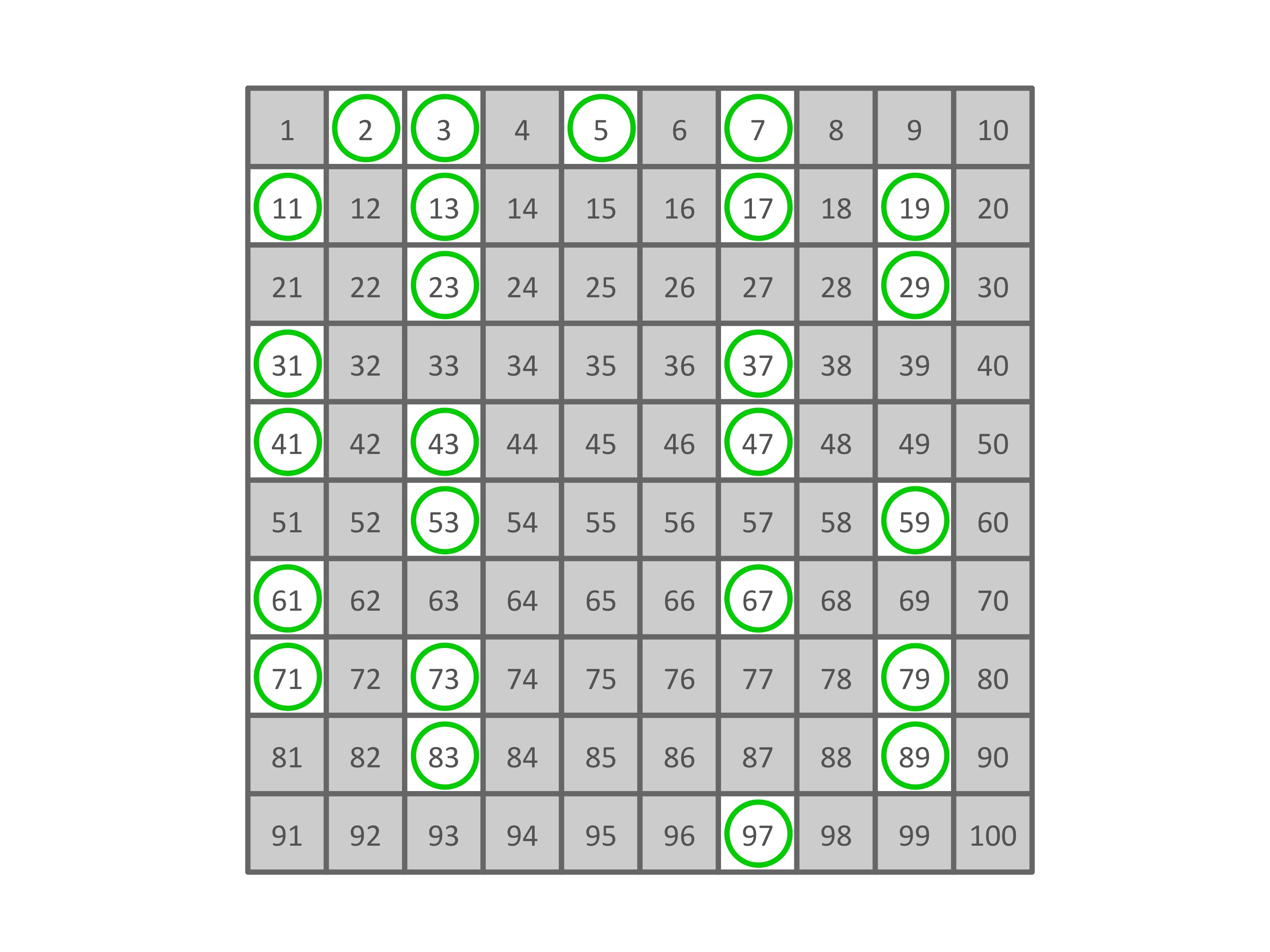

We could keep going like this all the way to $100$. (If we were using a bigger grid, we could go even further.) The composite numbers fall through the Sieve, and what we have left over – the circled numbers – are our primes.

But we can make this process even easier! At some point in our Sieve-making, the step of shading all the multiples of the current prime became trivial. Past $50$, all the next multiples of our primes were past the end of the sieve. So once we hit that halfway point, we could just stop and circle all the surviving numbers. We can do even better than that, though: we only need to check numbers up to the square root of the size of the sieve. (Read that again, slowly, and try to figure out why it’s true. Hint: look what happened when we marked the multiples of $11$.)

Anyway, here’s the resulting list of primes less than $100$:

$$ 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47, 53, 59, 61, 67, 71, 73, 79, 83, 89, 97 $$

The list proceeds in skips and hops of irregular length. There’s no clear pattern to the primes – we can only guess where exactly the next one might land.

For that matter, how do we know for certain there’s a “next one” at all? Might the list just stop at some point? Is there a biggest prime? After all, it makes intuitive sense that primes should become scarcer as they get bigger.

It turns out that there are an infinite number of primes: there is no “biggest” one, because if there were, you could always find one that’s bigger. We can prove it, too!

We’ll start by assuming that there’s a biggest prime, so that if we make a list of all the primes we’ll eventually get to the end. Now let’s use this list to build an even bigger number that has to be prime. What we’ll do is multiply all the primes in our list together, and then add $1$. This new (huge) number isn’t divisible by $2$, because it’s $1$ more than a multiple of $2$; it’s not divisible by $3$, because it’s $1$ more than a multiple of $3$; it’s not divisible by $5$, because it’s $1$ more than a multiple of $5$; and so on through all the primes on our list, all the way up to the biggest prime. Therefore, our new huge number must be prime. But that makes no sense! We assumed there were no primes bigger than the last prime on our list, and now we’ve contradicted ourselves by saying there’s something bigger than the biggest. So our assumption must be wrong. There is no biggest prime.

“Okay,” you might say. “So we can just use this method to keep generating more primes, right? We can start with, say, $(2 \times 3 \times 5) + 1$, and calculate it out to $31$, and hey presto, it’s prime!”

Not necessarily. The numbers you’re talking about, where you multiply the first $n$ primes and then add $1$, are called Euclid numbers, and they’re not always prime (though they certainly can be, as in your example).

“Why not? Isn’t that what we did in our proof just now? We built a Euclid number and knew it had to be prime?”

Well, not quite. See, we only knew our new huge number was prime because we assumed that we knew what the biggest prime in the world was. But now we know that our assumption was false. So if there’s another prime between our “biggest prime” and our Euclid number, it could potentially gum up the works. Just say we multiply all the primes up to $13$ and make a Euclid number from that:

$$ (2 \times 3 \times 5 \times 7 \times 11 \times 13) + 1 = 30030 + 1 = 30031 $$

But $30031$ is not prime: $30031 = 59 \times 509$. This is an example where two primes ($59$ and $509$) between our “biggest prime” ($13$) and our Euclid number ($30031$) happened to be factors of our Euclid number.

“Okay,” you reply. “So that algorithm doesn’t always give us primes. Is there some other algorithm that will?”

This is a very good question, and one that has baffled mathematicians for years. There have been many valiant attempts at solving this conundrum.

For instance, a mathematician named Pierre de Fermat came up with this formula:

$$ 2^{2^n} + 1 $$

Fermat thought that this formula would always result in primes, no matter what $n$ you stuck into it. And the first four Fermat numbers, as they’re called, are indeed prime. (This was back in the days before calculators, so Fermat figured that all out on paper, which was a big deal.) But the formula breaks down at $n = 5$:

$$ 2^{2^5} + 1 = 2^32 + 1 = 4294967297 = 641 \times 6700417 $$

In fact, all the Fermat numbers bigger than this that we’ve calculated so far have been composite. So that didn’t work.

Another such formula is this one, invented by a person named Marin Mersenne:

$$ 2^n - 1 $$

Numbers in this form are called Mersenne numbers, and if a Mersenne number is prime it’s called a Mersenne prime. The first few Mersenne primes are $3$, $7$, $31$, and $127$.

Not every $n$ that we plug into the formula will result in a prime number. But it turns out we can be even more specific: if $n$ is composite, then $2^n - 1$ must also be composite. Does that mean that plugging in a prime $n$ will give us a prime Mersenne number? No, not always. If we let $n = 11$, for example, then we get

$$ 2^n - 1 = 2^{11} - 1 = 2047 = 23 \times 89 $$

So a prime $n$ doesn’t guarantee a Mersenne prime. Nevertheless, Mersenne primes are still very important – most record-breaking prime numbers are Mersenne primes. The biggest number so far that we know to be a prime is

$$ 2^{57,885,161} - 1 $$

That is an absolutely ginormous Mersenne prime. When you calculate it out, it has over $17$ million digits. Just to get a sense for how ginormous that is, the number of atoms in the observable universe has about $80$ digits.

The distribution of prime numbers is still at the cutting edge of mathematics today. The most recent development in the quest to find a formula for them is called the Riemann hypothesis, which is one of the greatest unsolved problems in mathematics today. The Riemann hypothesis basically says that the numbers that make a certain function equal to zero all have to be in the form $\frac{1}{2} + t\sqrt{-1}$ (for some $t$); these numbers can then be used in another formula that tells how many prime numbers are less than any given number. It might sound a bit roundabout, but if it’s proven, the Riemann hypothesis would give us a way to predict the distribution of prime numbers with remarkable accuracy. So far it’s been over $150$ years, and nobody’s proven it yet!

Prime numbers, those that can’t be broken down into smaller factors, are simple to start playing with but intriguingly complex to fully master. Who knows – maybe you’ll be the next one to discover something new about these enigmatic numbers!