Leapfrog - Solution

If you’ve played with this problem for a while, you might have noticed that getting to (1, 1) is quite troublesome. Every time the frogs seem to get close, they just miss the mark.

There’s a reason for that!

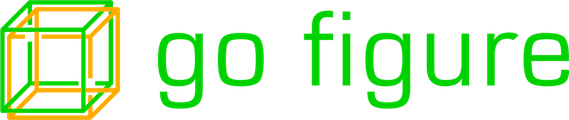

To see why this is so hard, let’s take a closer look at what a leap looks like.

To get from one frog’s location to another frog’s location, you can always take some number of steps to the right and some number of steps up. Let’s call these changes x and y. If the first frog’s coordinates are (a, b), we can write the coordinates of the second frog in terms of a, b, x, and y: the second frog is at (a + x, b + y). (Take a minute to convince yourself this still works when x and y are negative or zero. Draw a picture to see what that looks like.)

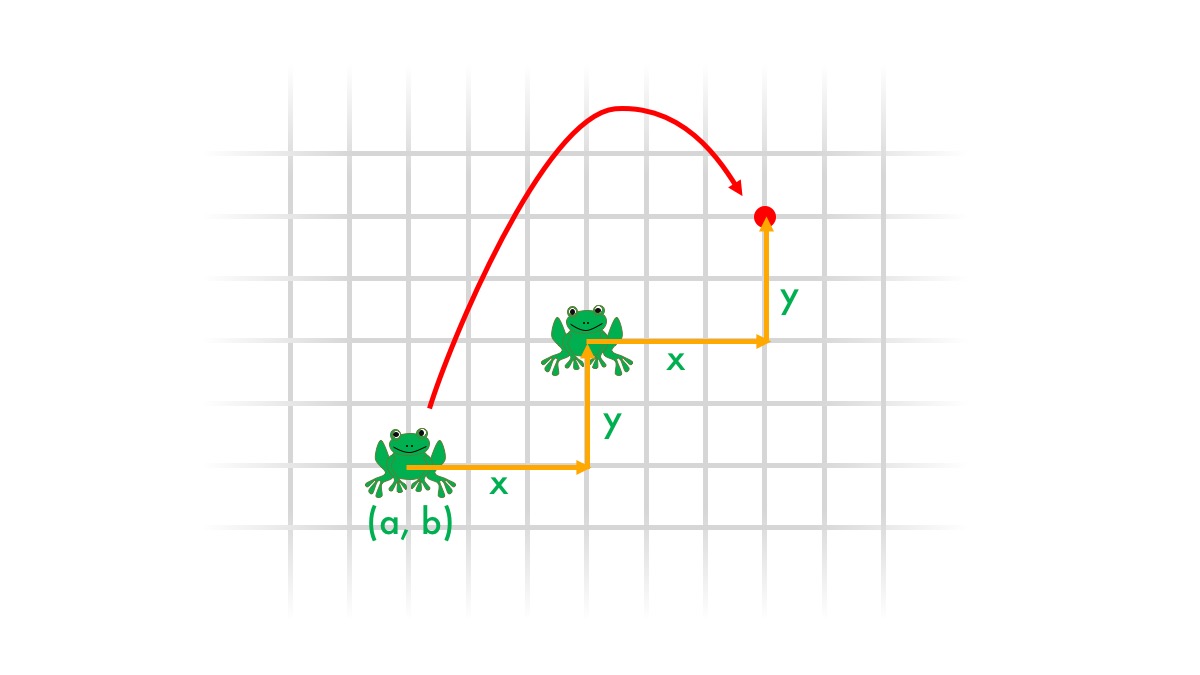

Now to get from the first frog’s location to its landing place, we take that x and y and go twice as far right and twice as far up:

So our landing place is at (a + 2x, b + 2y).

Now here’s the key: 2x and 2y are both even, and odd + even = odd and even + even = even. So, for instance, if a is even and b is odd, a + 2x will be even and b + 2y will be odd, no matter what x and y are. In other words, it doesn’t matter where the leapee is relative to the leaper: a frog starting at (even, odd) coordinates such as (0, 1) will always land at (even, odd) coordinates such as (4, -1). Likewise, a frog starting at (even, even) coordinates such as (0, 0) will always land at (even, even) coordinates such as (2, 0), and a frog starting at (odd, even) coordinates such as (1, 0) will always land at (odd, even) coordinates such as (-1, 2). (The technical term here is parity, meaning evenness or oddness. Leaps preserve the parity of the leaper’s coordinates.)

But (1, 1) is (odd, odd). That doesn’t match the pattern for any of the frogs' starting coordinates in this game. So no matter how long the frogs play this game of leapfrog, they won’t be able to get to (1, 1) – it’s actually impossible given the starting configuration.

Can you add one more frog – not at (1, 1) – so that getting to (1, 1) is possible?

As an extra challenge: we’ve proved there are some coordinates the frogs can’t get to, but we haven’t proved what they can get to. (Notice that if we put all three frogs on a line, they’ll stay on the line no matter what jumps we make.) If the frogs start at (0, 0), (1, 0), and (0, 1), what coordinates can they reach?