Choosing a Route

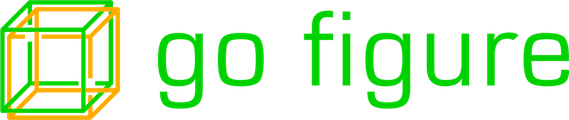

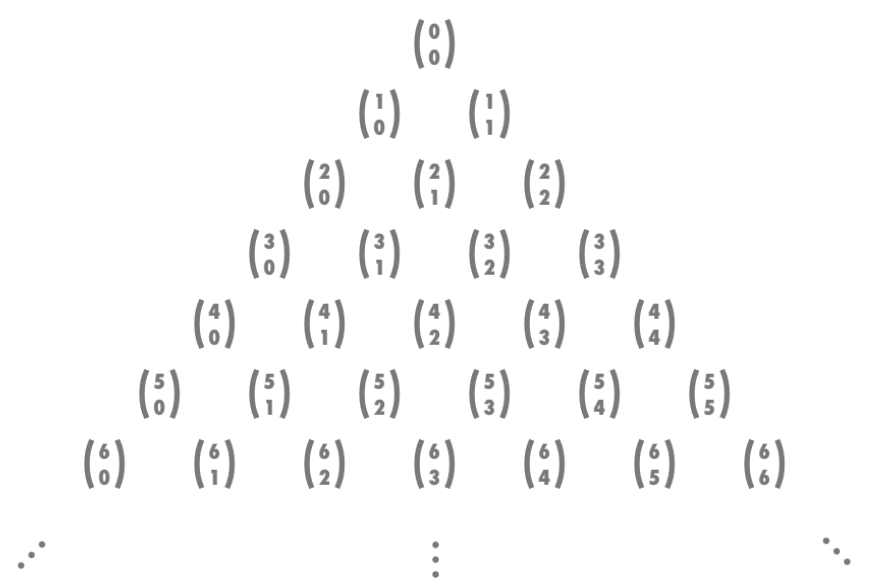

Here, for reference, is our good friend Pascal’s Triangle.

Remember choosing? Then you recall how to calculate

$$ \dbinom{6}{0}=1, \dbinom{6}{1}=6, \dbinom{6}{2}=15, \dbinom{6}{3}=20, \dbinom{6}{4}=15, \dbinom{6}{5}=6, \dbinom{6}{6}=1. $$

Look at those numbers you got, and look back at Pascal’s Triangle. Go ahead, scroll up and look.

Now why on earth…?

If you think it’s a fluke, do some more calculations. I’ll wait.

Pretty, is it not?

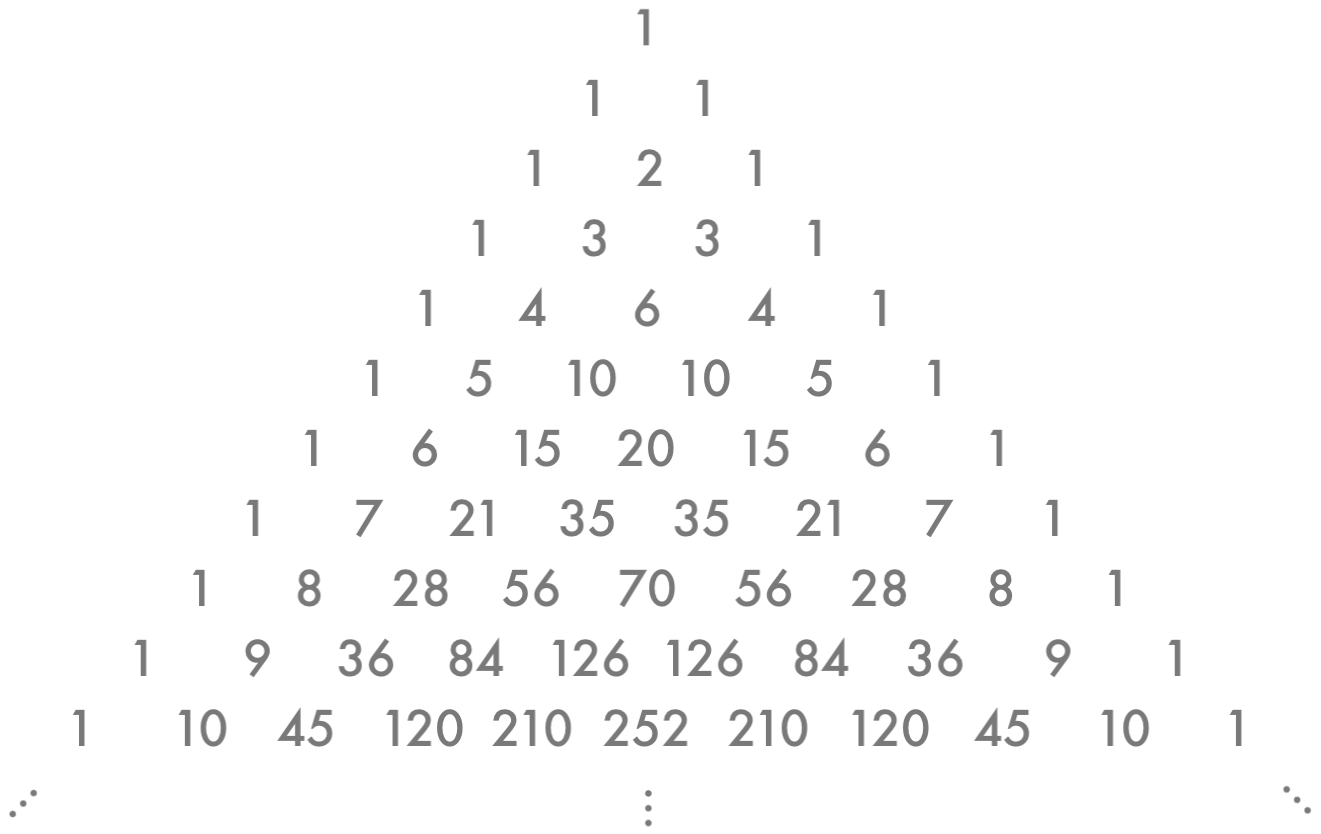

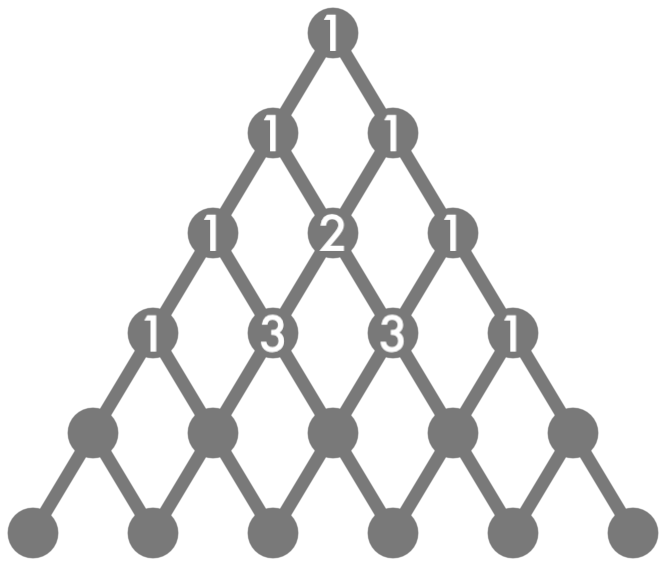

In order to get to the root of this elegant mystery, let’s look at Pascal’s Triangle another way. Specifically, we want to know how many ways there are to get to a number in Pascal’s Triangle if we start at the very top and can only go down-left or down-right. Let’s replace each number in the triangle with a dot, and connect the dots like this:

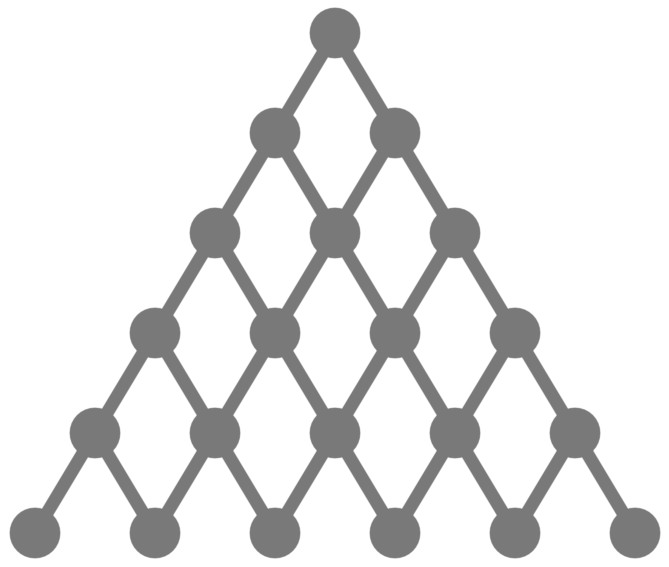

Now let’s fill in how many ways there are to get to each dot. We start at the very top dot, Row 0 – there’s only one way to get there. Now for Row 1, the left dot can only come from the topmost 1, and the same goes for the right dot. Then for Row 2, the dots on the outside can only come from the dots above them; but the dot in the middle could come from either of the two dots above it, so it has 2 possible paths.

Now for Row 3. Again, the outer dots can only come from one place. But now the inner dots could come from either a 1-path dot or from the 2-path dot. The total number of paths for it, then, is $1+2=3$. Now we have:

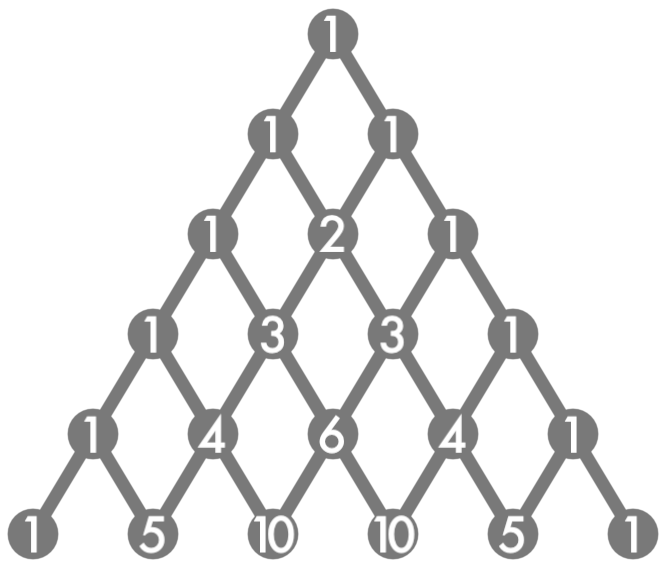

If we keep doing this, filling in the number of ways to get to each dot, we get this:

Look familiar? Indeed, Pascal’s Triangle is about more than adding numbers: it’s about counting paths.

With that said, we still haven’t explained how this relates to the whole choosing thing. Perhaps you see now that it’s time to pull out our old friend path counting.

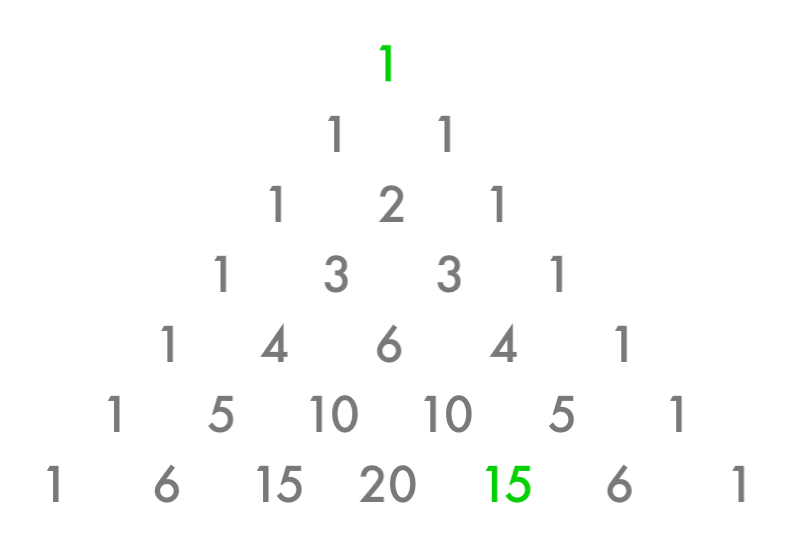

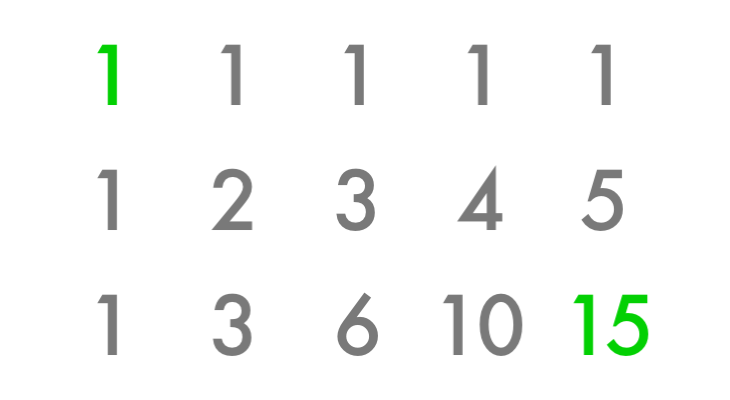

Let’s start with an example: Row 6, Spot 4. The relevant section of Pascal’s Triangle looks like:

Row 6 Spot 4 is in green (remember, we start counting at 0!), and so is the very top 1 where we start. To make this easier to see, let’s rotate Pascal’s Triangle a bit.

Now we’re trying to get from the green 1 to the green 15 by only going down or right. Just like we saw when we talked about path counting, we can ignore the numbers that are too far south or too far east. And what’s left?

We make a total of six steps, four of them eastward. In other words, it’s $6$ choose $4$. The number in Row 6 Spot 4 is $\dbinom{6}{4}$. Now you see why we start counting at $0$?

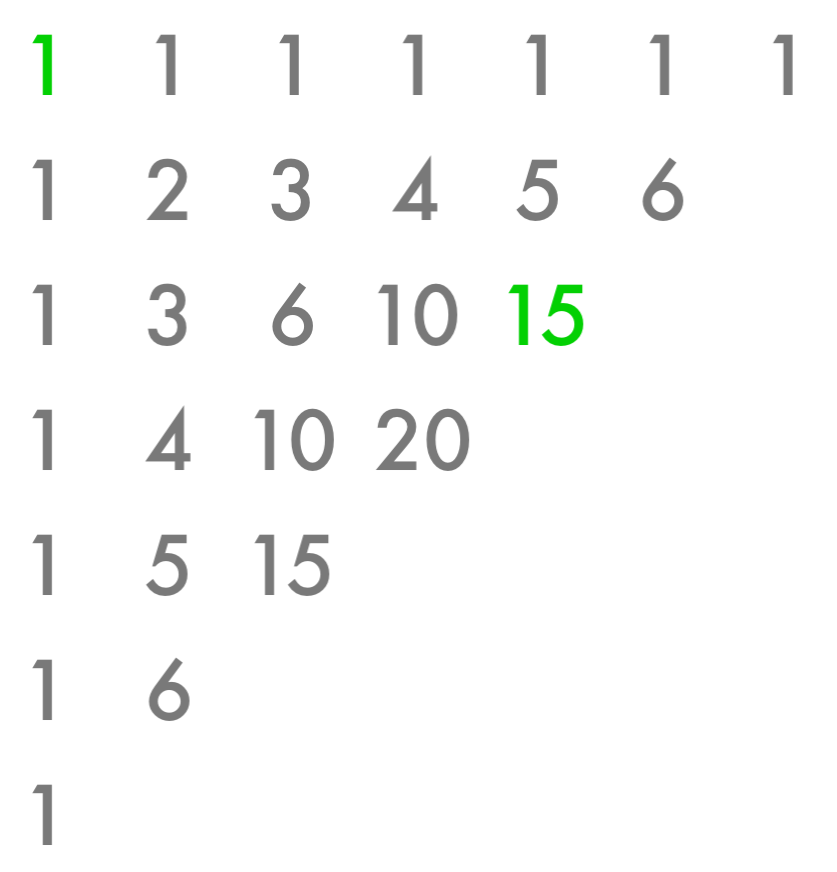

There’s nothing special about us picking Row 6 Spot 4, of course. We could have gone through this process for any number in Pascal’s Triangle. If we replace all the numbers with their row-choose-spot equivalents, we get:

This absolutely gorgeous diagram leads us to an incredibly simple identity called (appropriately) Pascal’s Identity. It looks like this:

$$ \dbinom{n}{r}+\dbinom{n}{r+1}=\dbinom{n+1}{r+1}. $$

This is really just a mathematical way of saying that each number in Pascal’s Triangle is the sum of the two numbers above it.

There are other lovely counting identities that Pascal’s Triangle helps us prove, most notably the Hockey Stick Identity and the Binomial Theorem… but that’s a story for another time.