Fibonacci Rabbits

Let’s talk about rabbits. Specifically, let’s investigate a biologically unrealistic rabbit population that is multiplying like… well, rabbits.

Every month, the following rule is applied: - Each pair of adults produces a new pair of baby rabbits. - Each pair of baby rabbits matures into a pair of adults.

We can abbreviate these rules by using “W” for a pair of adult rabbits and “w” for a pair of baby rabbits (“w” signifying two pairs of rabbit ears, of course).

The population starts with a single pair of baby rabbits. The question we want to explore is this: As the months go by, how does the rabbit population grow?

Let’s compute the rabbit population for the first few months and see if we can see a pattern. Looking for patterns is very useful in math – it can help show us where to investigate a problem further.

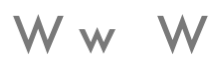

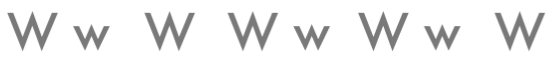

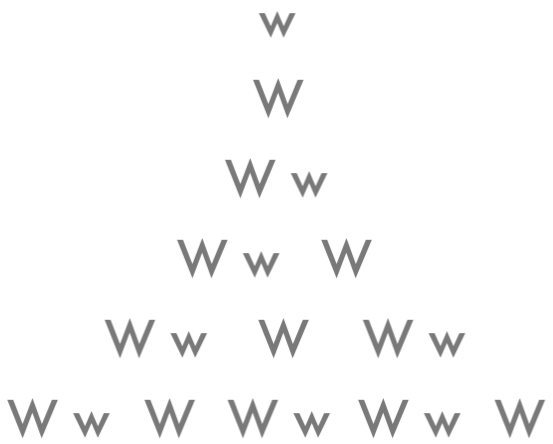

At the first month, we are told, there is one pair of baby rabbits.

At the second month, the baby rabbits have grown into adults. One pair still.

At the third month, the first pair has produced a pair of baby rabbits. Two pairs total.

At the fourth month, the adult pair has produced another baby pair, and the previous baby pair has grown up. Three pairs.

At the fifth month, both adult pairs have generated baby pairs, and the previous baby pair has grown up. Five pairs.

One more time: At the sixth month, all three adult pairs generate baby pairs, and both baby pairs grow up, and we have eight pairs.

Putting all this together, we can count the number of rabbit pairs in each generation:

$1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8$ – you recognize that number sequence?

But why are the Fibonacci numbers appearing here? And does this pattern continue on forever?

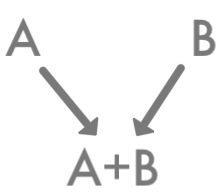

Let’s investigate this problem a little more deeply. In order to answer our questions, we’ll need to look at the problem a little differently. We’ll need to use the fact that each generation consists of some number of pairs of adult rabbits and some number of pairs of baby rabbits. Those are the only categories, and they don’t overlap, so we can find the total number of rabbit pairs by adding the number of adult pairs and the number of baby pairs.

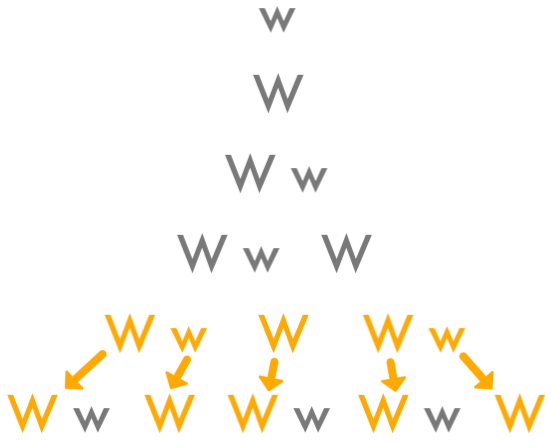

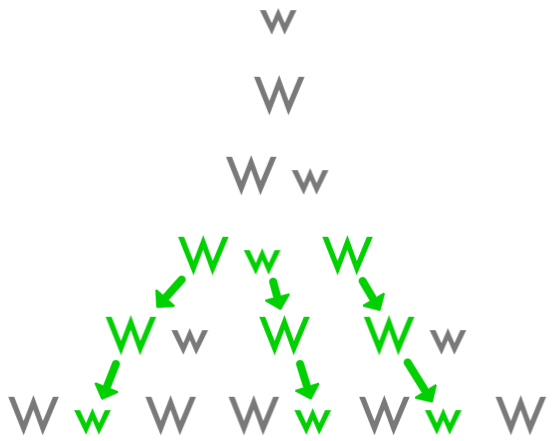

Let’s start with the adult pairs. What do we know about adult rabbits? Well, we know that they’re adults, so by definition they must have had time to grow up. Specifically, we know that they must have been around for at least one month. For example, all the adult rabbits in Generation 6 below had to have existed in Generation 5.

But when we draw it out like this, we see something else as well: Every rabbit pair in Generation 5 is an adult by Generation 6. Either it’s an adult pair that’s going to still be an adult pair, or it’s a baby pair that’s going to grow up to be an adult pair. And here we realize something important: This one-to-one correspondence, as it’s called, means that we can count the number of pairs of adult rabbits in Generation 6 by counting the total number of rabbit pairs in Generation 5.

Okay, that’s very convenient. Now what about the baby rabbit pairs? They haven’t existed for a whole generation, but they’re not some random number dropped out of the blue. Remember our rule:

It tells us that each baby pair comes from an adult pair in the generation before it. And we also know that every adult pair in that generation before is going to produce a baby pair in the next generation. So we can count the number of baby pairs in any generation by the number of adult pairs in the previous generation. And how do we count the number of adult pairs in any generation? We just figured this out – we count the total number of rabbit pairs in the generation before! So we can count the number of baby rabbit pairs in some generation by counting the total number of rabbit pairs two generations before.

Okay, so we count the number of adult rabbit pairs by counting the total number of rabbit pairs one generation before, and we count the number of baby rabbit pairs by counting the total number of pairs two generations before, so to find the total number of rabbit pairs we add those two categories. And we end up adding two consecutive generations to get the next one. There’s our Fibonacci recursion! That’s why we were seeing that pattern! And because we started with $1+1$, we’re going to keep getting Fibonacci numbers for however many months we choose.

This sort of Fibonacci recursion appears in lots of surprising places. More problems coming soon!